CHAPTER 4 - The White Snake to Nowhere

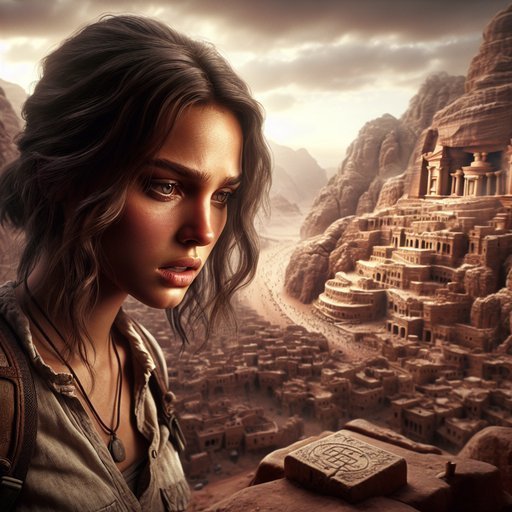

Before dawn under a half-moon, Barbra and her taciturn driver Salim reach Detwah Lagoon to test the clue, “When water leaves, breath returns.” In tight jeans, tank top, and blue-and-white Asics beneath a floral denim jacket, she aligns her copper disc with a tide-carved spiral and a red-resin recess. A small cavity yields a goatskin strip showing twin spirals and an instruction to follow the “white snake” sandbar to a mangrove “throat.” The lagoon exhales warm air from a narrow vent and the disc hums, but nothing opens, and a sudden tide forces a retreat. Details betray the find as a plant: the resin’s scent isn’t Socotra’s dragon’s blood, the goatskin looks new, and the carvings are too sharp. Realizing she’s been led astray by an unseen watcher, she starts over, returning to her room to reexamine the original amulet, sea-glass shard, and disc. Overlaying them suggests the “other breath” lies inland near Hadibu’s limestone and perhaps east toward Arher’s dune rather than at Detwah. As the pre-khareef wind moans and the cliff’s hum thickens, another cryptic message slides under her door, warning her again about the monsoon and hinting that the Door breathes inland, leaving Barbra poised to pivot her hunt.

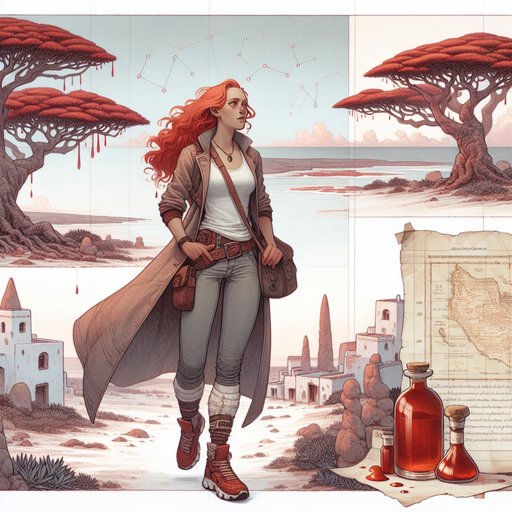

Before dawn the half-moon hung like a sliced pearl over Detwah Lagoon, its reflection wavering between the pale backs of ripples and the exposed ribs of coral. Barbra cinched the cuffs of her floral denim jacket against the pre-khareef damp and tucked a stray lock of red hair behind her ear; she’d tied it back in a practical knot before they left Hadibu. She could feel the freckles across her nose heaten in the cool air, a little constellation she never learned to like, though the darkness made them mercifully faint. Her blue-and-white Asics sank just enough into the cool, powdery sand to squeak, and the copper disc in her pocket tapped against her thigh with each step.

The lagoon breathed gently, water slipping out toward the mouth as if whispering to her: when water leaves, breath returns. Salim waited with the engine off at the edge of the flats, his shoulders hunched inside his faded jacket, hands sewn into silence on the wheel. He had driven her west in a drowsy drift, headlights flashing over goats and the occasional sleeping camel, neither asking nor answering much. Now, in the growing gray, Qalansiyah still slept, its homes tucked like shells in the fold between dunes and limestone.

Fishermen’s skiffs were beached like ribs bleached by a relentless sun, and mangrove roots clawed the waterline where the tide had already begun to slide away. Barbra inhaled the faint incense that sometimes threaded the wind here and felt the memory of the cave above Hadibu surge up: the warm exhale when she held the disc just so, the whisper—hurry—caught in stone. She ranged along the edges of the lagoon while the sky softened, scanning for anything like the spiral-and-three-notches carved into that north-coast blowhole days ago. Her boots whispered across seams in the hardpack, and she crouched when a tide-slick slab shone at her like a wet coin.

There it was: a weather-softened spiral, three little nicks notched into the outermost arc, and a pocket of resin hardened into a flat red tear. She set the disc on the stone, aligned the notches with the half-crescent mark etched into her new goatskin sliver, and turned until the moon’s reflection lay somewhere between true and imagined. The wind found her neck, and from a crack in the limestone ledge a breath of warmer air sighed out, just enough to make the hairs on her arm rise. “Here,” she called softly, and Salim killed the pretense of distance to pick his way across, boot soles leaving dark ovals on the sand.

She pressed carefully at the hardened resin and felt a give, the way a long-locked cabinet yields when you finally twist the right way. A click, faint as a lizard’s footfall, and the stone shifted more by suggestion than by movement; behind it, a shallow cavity wobbled with the smell of long-dried sap. Inside sat a clay jar no bigger than her fist, stoppered with a lid sealed in red. She thought of the elderly market woman’s palm-woven amulet and the way the goatskin had waited in its hollow, the way trust had to be earned here like an inhalation.

She worked the jar stopper free and eased out a tightly rolled strip of goatskin, its edges uneven, its ink dark and slightly oily. Two spirals stared up at her, twinned swirls like coiled snails touching, and a sketchy line curved between them with a neat inscription in the same careful hand as the palm knot: follow the white snake to the throat. Barbra felt a flicker of triumph; the line was shaped like the sandbar she knew emerged here at low water, a pale ribbon threading across the flats. She glanced up instinctively and caught a stilled silhouette on the distant shoulder of a dune—maybe a herder, maybe no one—and her spine tightened.

Being watched was never new, but on Socotra it carried the weight of families and years. The lagoon continued to empty itself with patient purpose, and just as the eastern horizon blushed, the sandbar lengthened and gleamed like a bone. “The white snake,” she said, and Salim’s eyes followed it though his mouth stayed flat. They made their way out along the paling path, water lapping at her ankles, crabs ticking away from her toes like wind-up toys.

Mangrove roots brushed a darker lip of stone where the bar tapered, and from a tight seam in that limestone a breath pulsed—warmer, wetter, layered with the mineral odor she now knew as the island’s subterranean signature. Barbra lifted the copper disc and felt it prickle against her palm as the breath teased its edge. She set the disc to the stone where a hairline suggested a seam and turned it, aligning the notches to the north by habit, then to the moon again, then to the curve of the sandbar like a compass built by poets. A harmonic rose, more felt than heard, like the way a seashell pretends to own the sea; the disc thrummed and warmed, dislodging a faint memory of another door in another place where the world had temporarily let her in.

She pressed, breath held, and the warm air thickened as if swelling toward a new pitch. Nothing moved. The lagoon’s emptying paused, quivered, and a sudden sluice of returning water slapped the sandbar’s waist, cold and unceremonious. “Back,” Salim said, finally voicing the simplest truth, and they stumbled away ankle-deep, then knee-deep, as the flats shrugged themselves into motion.

Barbra held the disc high and awkward and felt laughable for it, the way she sometimes felt in a pencil skirt and Louboutins when a night had lasted too long and love had lasted too little. By the time they made the shore, the harmonic had faded into the nagging buzz that had plagued her at the wrong blowhole two days earlier. She stood with water running from her jeans like a second tide and looked back at the mangrove mouth, the stone face blank as a closed eye. If this was a door, it was not opening to her today.

They waited, because that’s what patience looks like when you don’t yet know you’re wrong. The sky blued, the half-moon bled into morning, the heat began its rehearsals. Barbra squatted and shaved a curl off the jar’s red seal with her nail and brought it to her nose. The scent was wrong, not the smoky, metallic sweetness of Socotra’s dragon’s blood resin she’d learned to identify, but a flat, tired gum like a market fake.

The goatskin was supple in a way old skin is not, and the spirals were scored too cleanly; even the spiral on the slab appeared sharper than it should, as if sand and time had been asked to look the other way. She straightened slowly, memory of the first amulet’s breath of incense still lodged in her like a lodestar. “It’s planted,” she said, and Salim’s lids lowered as if to concede what he’d suspected. Whoever had slipped the copper disc beneath her door, whoever had threaded the warning into her nights, had company—someone less patient, less careful with truth.

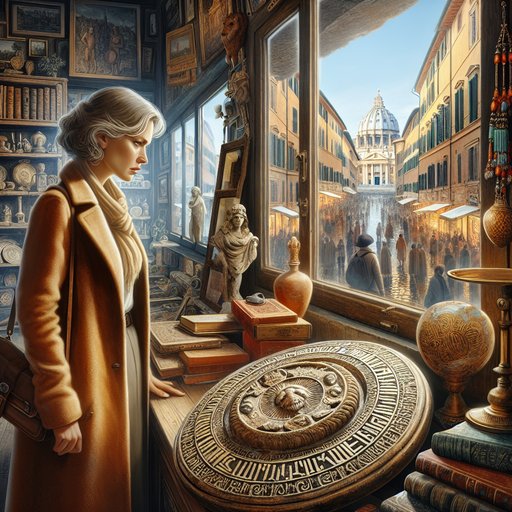

Barbra felt a flash of anger, hot and lonely, the kind she hadn’t allowed since childhood when she’d learned to pull her own shoes on and open the fridge without asking. It sharpened into resolve, as firm and clean as the edge of her disc. Back in Hadibu by late morning, she dumped her day’s failure onto the bed with the care of a curator: the disc, the first goatskin map-poem, the palm amulet, the sea-glass shard scratched with three notches, the false strip she now mistrusted. The guesthouse’s whitewashed walls held the heat like a hand and the fan clicked in an irregular rhythm that made her think of the cave’s hum.

She overlapped edges and arcs and let her eyes un-focus, a trick she’d learned on long walks alone across too-open places where patterns emerged if you stopped insisting. The sea glass’s notches aligned with the disc and then, surprisingly, with the angles of vents she’d sketched in the limestone above town, not with anything at Detwah. The half-crescent wasn’t a moon at all here but the curve of a dune she had seen at Arher where freshwater springs bubbled into the sea and the wind wrote long sentences in sand. She exhaled and felt something switch back on: start again.

Not because she loved futility, but because the integrity of the search demanded it. The cave above Hadibu had given her a true breath; the singer’s ditty had given timing, not geography; the rest had been someone else’s story, pressed on her with red glue. She pulled on a dry tank top and her tight jeans again, laced the same trustworthy Asics, and swapped her floral jacket for a lighter one to climb in, the one with the scuffed elbow she’d earned in a gorge years ago. If the Door of Winds had a sister breath, it was inland first—then east, where dune and spring made their own quiet pact.

As she gathered her things, a soft slide against the floor broke the room’s rhythm. An envelope crept under the door, its edge trembling with the fan’s stray breeze; inside, a strip of braided palm fiber fell into her hand along with a bead of genuine dragon’s blood resin that smudged her thumb with a sweet, iron scent. Two lines scratched into a sliver of bone read: Before the khareef, or not at all. The Door breathes inland.

Barbra’s skin prickled as the hum from the limestone above town thickened, as if answering its own name from far away. Was the true path finally lifting its head—or was the watcher only tightening the net?