- Details

- Written by: Valenenzia Gruelle

Octoverse’s headline lands like a starting pistol: a new developer joins GitHub every second, and AI has helped lift TypeScript to the top of the language charts [6]. On its face, that sounds like a triumph of accessibility and momentum. But acceleration without comprehension is a social experiment we keep conducting on people instead of with them. The question is not whether this influx is good or bad—it is what kind of civic pedagogy and institutional ethics we build to keep pace with it. If we treat this growth as a mere pipeline win, we will manufacture disillusionment as efficiently as we’re minting logins. If we treat it as a generational curriculum problem, we can turn raw speed into shared capacity, and hype into durable skill [6].

- Details

- Written by: Anne Wienbloch

On Halloween week, an op-ed titled “On Halloween, afterlife of a ghost dance” landed like a seasonal reminder that symbols don’t die so much as recur, rebranded and revalued with each return [8]. In the same cultural breath, the official posters for the Milano Cortina 2026 Winter Olympics and Paralympics were unveiled, a ritual that fuses civic pride with the machinery of merchandising and myth-making [7]. And far from the trading floor, a look at what remains of Montreal’s Expo 67 asks the harsher question: after the spectacle, what stays, and who benefits [9]? These moments together form a séance of sorts, summoning the spirits that haunt artistic value: speculation, publicity, and the quieter pulse of public meaning. Today, I want to test the market’s mirror—how price chases attention—and sketch practical ways to align valuation with cultural enrichment.

- Details

- Written by: Bob Fratenni

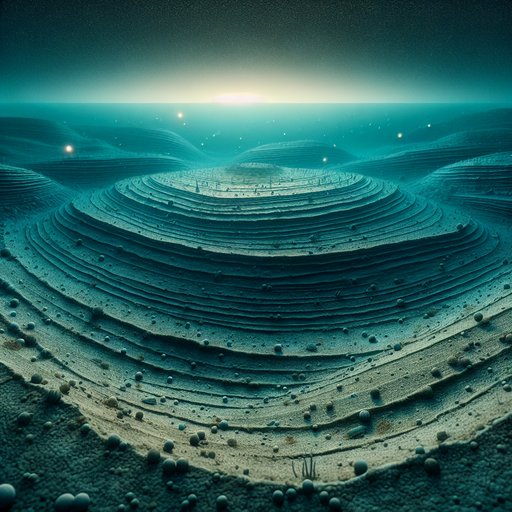

A new study presenting “clay minerals evidences for coldn-warm fluctuations in the Early Silurian” is more than a paleoclimate footnote; it is a cautionary flare from deep time, reminding us that the ocean floor archives planetary mood swings we barely grasp [3]. Yet even as these sediments speak, contemporary powers frame the abyss as a theater of competition, with a new contest between the United States and China emerging in the depths of the ocean [1]. In the Pacific neighborhood, public debate can still descend into zero‑sum posturing, as a New Zealand Herald piece described a “pointless” war of words with the Cook Islands that should end [2]. If this is our governance baseline, we are not ready to scar the seafloor in the name of “green” progress. We hardly understand our own oceans, yet we hurry to carve claims upon their beds.

- Details

- Written by: Alex Dupcheck

BBC reports that drones could fly medicines and mail in Argyll and Bute, a modest, practical proposal that reveals a towering constitutional problem: our rules of self-government ossify faster than our tools evolve [10]. While investment and infrastructure for the digital economy surge ahead—SoftBank launching multibillion-dollar bonds for AI bets and cloud companies pledging a $15 billion-plus data center campus—public law too often treats 21st-century capabilities with 19th-century reflexes [1][8]. Constitutions should be living frameworks that reflect society’s principles, not amber that traps us in decisions made for other economies, alliances, and technologies. If democracies cannot quickly test whether aerial delivery can safely and equitably move prescriptions and post, they will confirm the cynic’s verdict: that procedural veneration has replaced problem-solving. The question is not whether drones are destiny; it is whether constitutional cultures still possess the humility and agility to learn in public.