CHAPTER 5 - The Other Breath and an Unlikely Ally

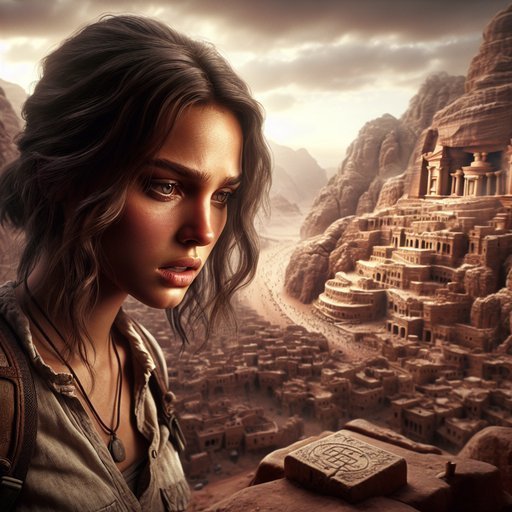

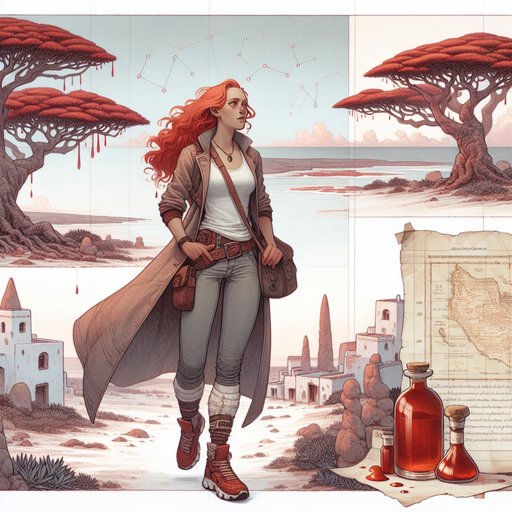

Haunted by the cliff’s low hum and a cryptic note that the Door breathes inland, Barbra pivots from Detwah to the limestone heights east of Hadibu near Arher’s dune. Dressed in tight jeans, tank top, floral denim jacket, and her blue-and-white Asics, she carries the copper disc, the original amulet’s goatskin strip, and the sea-glass shard. With Salim, the taciturn driver, she follows the rising pre-khareef wind and finds an old spiral-and-three-notches carving marked by genuine dragon’s blood resin. When a perceptive young woman from the fishing hamlet—who once warned her away—appears with proof of Keeper ties, she unexpectedly offers help, testing Barbra’s integrity before guiding her to a hidden vent where two breaths—the ocean and an inland aquifer—periodically sync. The trio attempts a precise alignment of the copper disc, goatskin, and resin-marked sockets timed to the dual pulses, but the rock balks until Salim reveals a family-resin seal that completes the mechanism. As the stone shivers and a narrow slit exhales a deep chord, shadowy figures close in from the ridge. Barbra squeezes into the breathing crack toward a stair that descends, only for their light to gutter and the door to shudder, leaving her to choose between retreat and plunging forward into the Monsoon Door’s dark heart.

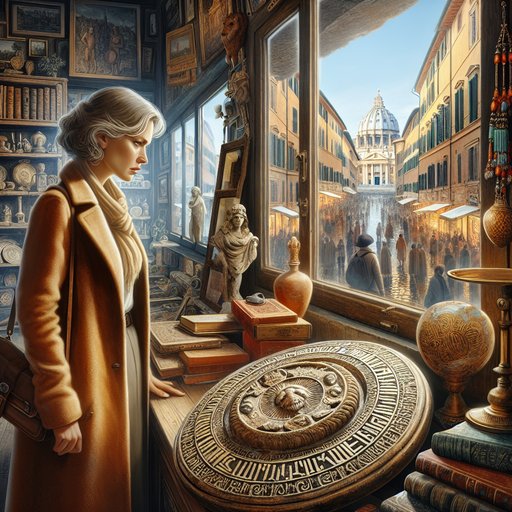

The hum returned before dawn like a memory she hadn’t invited, a low, steady breath tugging the curtains of her whitewashed room in Hadibu. Barbra sat on the edge of the bed in tight jeans and a black tank top, lacing her blue-and-white Asics with hands that remembered all the things she’d learned to do alone since she was four. The floral denim jacket hung from a chair, a soft armor that smelled faintly of dust and dragon’s blood resin from missteps the day before. She laid the original goatskin strip, the copper disc with its spiral and three notches, and the sea-glass shard on the bedspread, overlaying their symbols again until they suggested a diagonal toward the limestone east of town and the white tongue of the Arher dune.

The pre-khareef wind did not whistle today; it breathed, and it would not let her go. Salim was waiting by his battered pickup, the same thoughtful squint beneath the brim of his cap, as if he were staring into a wind no one else could see. He didn’t ask where; he simply eased the truck out past the market and the frankincense stalls, tires whispering over dust as the ocean fell behind and the interior rose in chalk and thorn. Bottle trees ballooned from the scrub like pink-lipped sentries, and dragon’s blood crowns shaded the stony ridges in shapes that looked like old maps of storms.

As they approached Arher, the dune spilled white into a turquoise bay, but what drew Barbra was the limestone above, the pale escarpment pocked with vents and swallow nests. With every kilometer the hum deepened, as if the island itself were clearing its throat to say your name. They parked near a freshwater trickle where goats had chiseled their hooves into the clay, and Barbra felt the air grow warmer as she climbed the ledges. Her freckles, which she always despised for how they announced her in any sun, prickled with heat and salt, but her long legs ate the stair of rocks with that slim, muscled stride she’d earned in a thousand wanderings.

A narrow fissure exhaled on her wrist like a patient sigh, and she held the copper disc over the breeze, listening for the thinnest harmonic. Nothing. She moved lower, then left, and there—a groove no wider than a thumbnail—wore the spiral and three notches, its lines softened by time, marked at the edges by flakes of dried red resin that smelled unmistakably of dragon’s blood. Barbra knelt, brushed grit aside, and felt the cliff beneath the symbol thrum like a stifled drum.

She set the disc into the spiral and turned until the three notches aligned with shallow sockets in the rock, but the fit was imperfect, or perhaps the breath was wrong. The goatskin’s inked half-crescent earlier had misled her, but the original poem spoke of “where the sea breathes twice,” and here it seemed to breathe, but not twice—at least not yet. She rocked back on her heels, tasting frustration, remembering other moments when she had to trust dead stones more than living people. That memory broke when gravel skittered above and a familiar figure descended with the grace of someone who belonged to ledges.

The young woman from the fishing hamlet wore a headscarf the color of the lagoon at dusk and a palm-woven braid sealed at one end with red resin. “You search in the right place, but you listen wrong,” she said, voice low, eyes bright with an appraisal that wasn’t unkind. She held up the braid; the resin bore a tiny impressed spiral with three notches. “I am called Sanaa.

My aunt keeps the stories. The men at Detwah planted tricks to turn you away—they don’t trust outsiders. I sent the sea-glass, but someone intercepted and wrote another path to confuse you. Will you promise not to take what is not yours?”

Barbra’s mouth was suddenly dry, but the promise rose easily because it was already true.

“I won’t steal your past,” she said, not bothering to hide the tremble she felt as the hum pressed at her ribs. “I want to understand it. If it needs to stay hidden, I’ll help keep it hidden. I’ve spent my life looking for doors I can close after I look through them.” Sanaa studied her freckles, her stripped-down face, her scuffed floral jacket, and something relaxed in her shoulders.

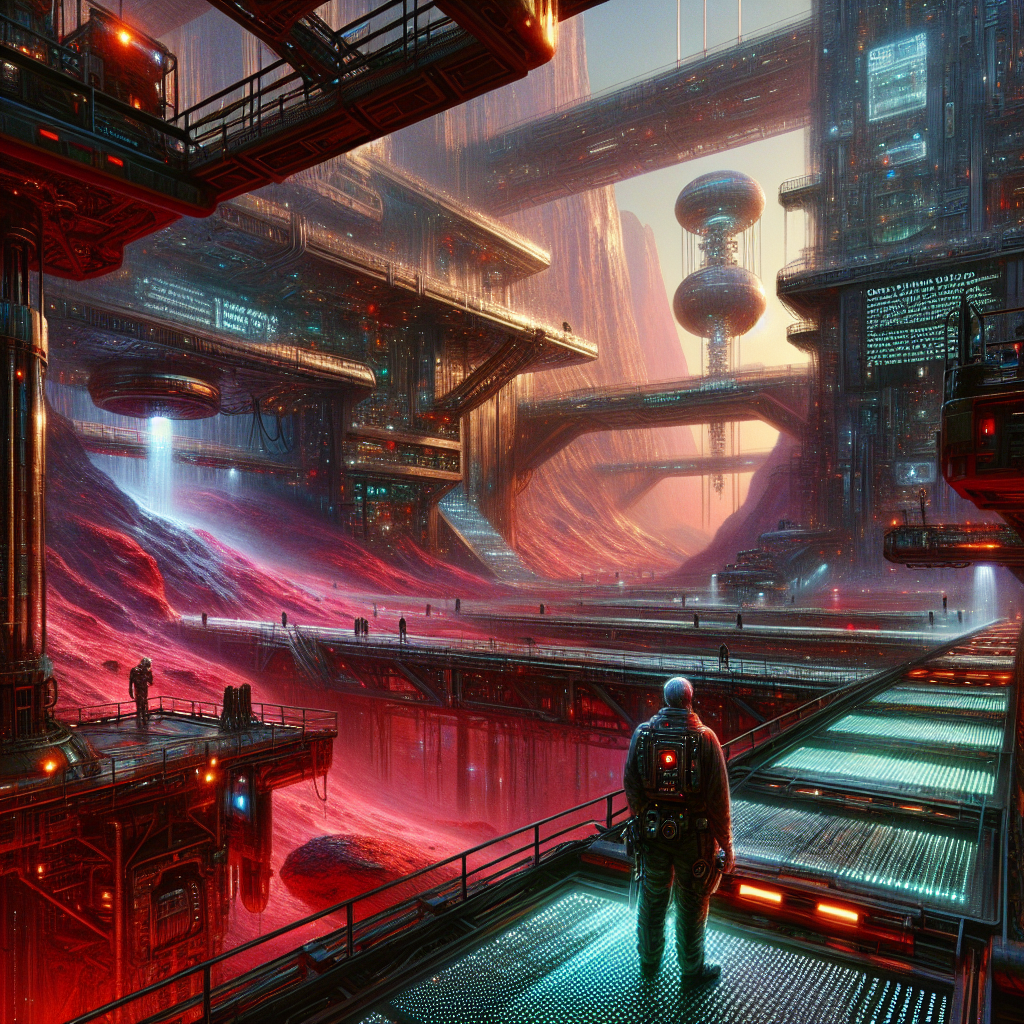

“Then listen for the second breath,” Sanaa said, and led them along a narrow shelf that overlooked the white dune below like a frozen wave. “These are not sea caves, not only. An inland vein of water moves beneath the limestone and breathes with pressure when the wind and tide meet the aquifer. Twice a day, sometimes once—two lungs.

When they match, the Door will answer. You need the resin’s right scent to wake it, and you need patience.”

They came to a crease where a cluster of sockets pitted the rock like stars. Sanaa sprinkled a pinch of vermillion shavings on a thin seam, and the true scent of dragon’s blood rose—wooded and metallic, not the sharp counterfeit Barbra had found at Detwah. Barbra placed the copper disc into the spiral again, this time overlaying the goatskin strip so that the inked line, old and faded, lined up with a fissure that glowed faintly with light refracted from the dune.

The wind deepened, then softened, and a colder breath threaded through it from within the stone. With a hitch in her chest, Barbra turned the disc a hair to match both beats. The ledge vibrated, but something resisted—a failing heartbeat that couldn’t find its pair. A question rose on Barbra’s tongue, and before she could ask, Salim, who had watched silently as always, stepped forward.

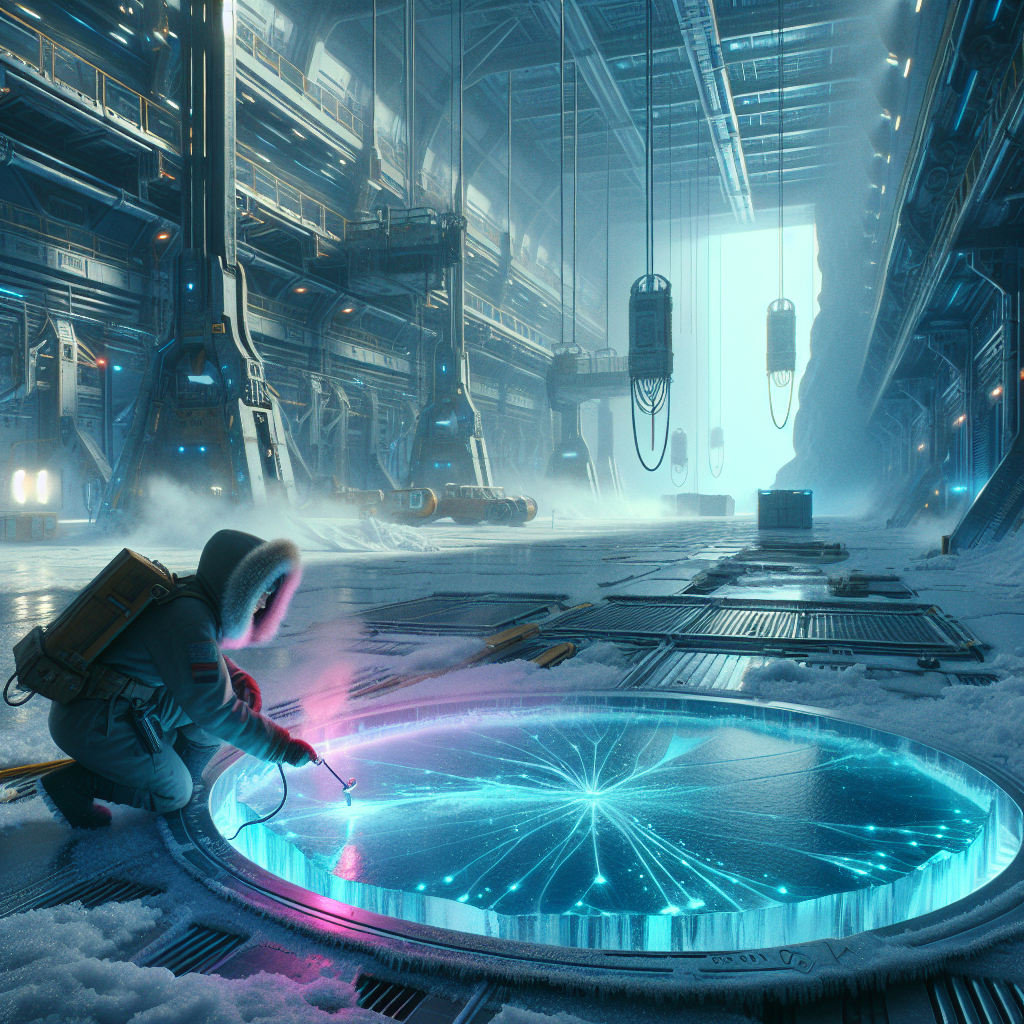

He reached into his pocket and brought out a lump of red resin molded around a small pebble, impressed with the same spiral and notches; it looked old, a pocket-kept memory shiny from years of handling. “My grandmother whispered stories when the wind came,” he said, gaze distant. “She told me to keep this only if a stranger heard the hum like family. I think she meant you.” With a shy gravity that struck Barbra more sharply than any warning, he pressed the resin into the uppermost socket.

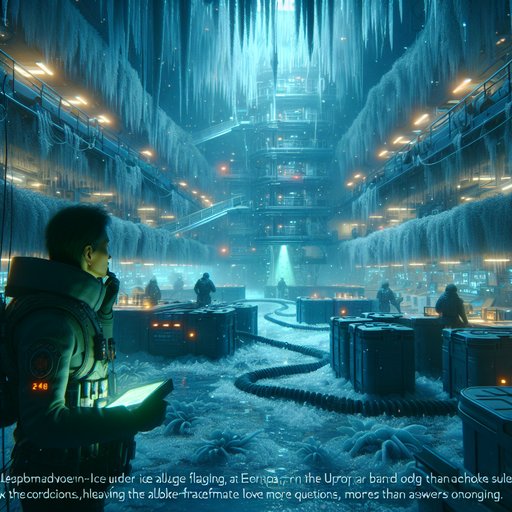

The stone gave with a sound like a jaw unclenching. Air rushed out, then in, a chord layered with warm and cool, salt and iron, desert and surf. A sliver of rock withdrew to reveal a seam just wider than a shoulder, and within it the breath rolled strong enough to stir hair and sting eyes. Sanaa touched the edge with her palm and nodded once, respect and sadness passing over her face.

“Before the khareef, or not at all,” she said, echoing the warning Barbra had found on the disc, and gestured for her to go first. Footsteps clattered on the ridge beyond, and three silhouettes crested the skyline—men with scarves pulled high, one limping, one tall as a doorframe, one carrying a short coil of rope. The watchers who had sown false signs at Detwah, or others like them, and they were too close to explain and too far to reason with. Sanaa’s jaw set; Salim’s eyes ticked to the truck down below and back to the slit; Barbra felt the old stubbornness that had kept her going after funerals and empty dinners rise like muscle under her skin.

She slipped the copper disc into her back pocket, tucked the goatskin strip into her jacket, and turned sideways into the breath. The limestone kissed her shoulders with chalk and moisture as she slid through. Inside, the air moved as if the hill were alive, warm on her cheek, cool on her other as she eased along a narrow corridor of calcite and compacted sand. The light fell away after two body-lengths, and then one more step found a shallow stair carved long ago, worn smooth by feet that must have come in pairs: keepers, perhaps, or families taking turns with secrets.

Sanaa squeezed in behind, then Salim, and the seam whisper-shut behind them; the outside voices went muffled, replaced by the deep breathing of stone. Barbra reached for the small headlamp she kept in her jacket pocket—because the girl who learned to do everything herself never traveled without a way to make her own light—and clicked it on. The beam ran across a relief of spirals and notches radiating like a compass over a basin of black water. A gust from below blew out the headlamp with a wet kiss and left them blind a heartbeat before another breath returned, cooler, measuring, ancient.

Above, the seam juddered, peppering them with dust as if the mechanism were preparing to close until the breaths matched again. Sanaa squeezed Barbra’s hand, a human anchor in moving air, and whispered, “We go when the two lungs speak together.” Somewhere ahead, something metallic clicked like a clock finding its hour, or a lock remembering its work. Barbra took a breath, tasted copper and salt and resin, and faced the dark where the Monsoon Door waited—was she brave enough to step when the breaths became one, or would the khareef catch her on the wrong side?