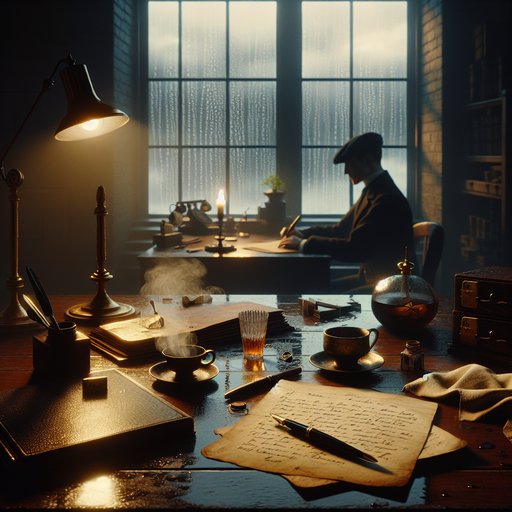

In a quiet office that smells faintly of paper and rain, a clerk keeps a ledger of what the living leave behind. Each entry is a small bridge over the gap mortality opens, a record of last things and the hands that held them. The citizens bring their objects and their urgencies, and the clerk listens as if listening could pin life to the page. It is an unglamorous vocation, this accounting of final fragments, but in the scraps and misunderstandings, in the items smudged with use, a pattern sometimes gleams, then vanishes. She cannot say what it means; perhaps meaning is the wrong shape for what she’s looking for. Still, as storms gather and rooms flood, as plants root in teacups and strangers remember the textures of other palms, she keeps writing, and the ledger grows heavy with lives neither large nor small, only lived, and finite.

On the day when the city weighs joy, they string the square with lanterns and drag old iron scales from their storerooms, their chains polished until they gleam like winter water. People bring what they think a good life is made of—loaves from shared ovens, ledgers of hours given to others, scraps from cathedrals they helped repair, a glove kept after a long winter of care. We gather because it is our way to turn questions into festivals. I come with an empty pocket and a smooth river stone, invited to lay it on one of the scales before dusk and to declare a way of living. The banners that fringe the square suggest many ways. The hourglass in the bell tower dribbles its pale sand, and I go walking to see what kind of weight my hands could bear.

On the night the city gathers to weigh what is fair, the basketball hoops in the old municipal gymnasium are winched to the rafters, and folding chairs spread like a paper fan over the varnished floor. They call it a citizens’ assembly, but the sign on the door says something more brazen: Weights and Measures. The council has built a system to divvy buses and homes and grants, and they want the people to decide how it should decide. It sounds clean, the way an abacus is clean, but the air hums with the mess of lives. Fairness, equality, justice—these are not words drafted in the quiet. Tonight they will be hammered against the grain of a modern city and the people who make it breathe.

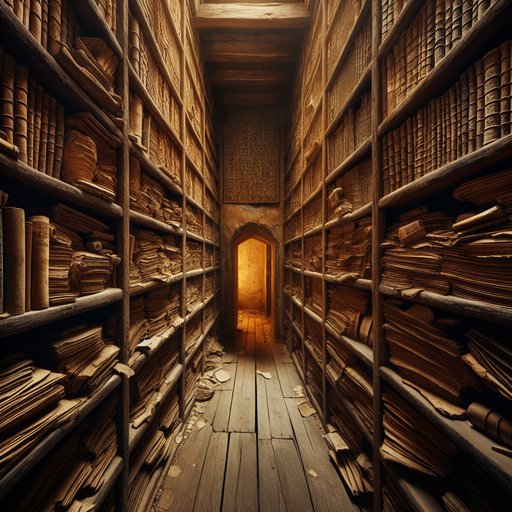

At closing time, when the lights of the city falter and settle into their long, sodium exhale, I slip into the library that keeps a little of every age. It is not a grand cathedral of knowledge but a narrow place with uneven floorboards and shelves that listen. I come because I am thirsty, and I do not know for what. In the low light, tablets and scrolls, sutras and codices lean toward one another like tired travelers telling stories they cannot finish. I put my hand on a cracked clay shard and feel heat, not of the bulb above me but of a hearth too old to remember. The room breathes, and the distance between then and now collapses like a tent taken down at dawn.