CHAPTER 1 - The Dragon’s Blood Cipher

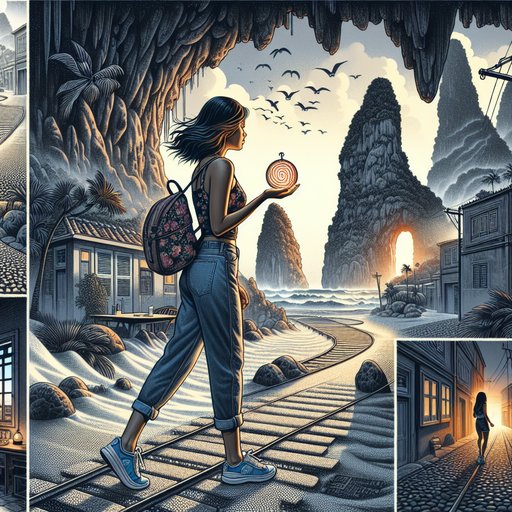

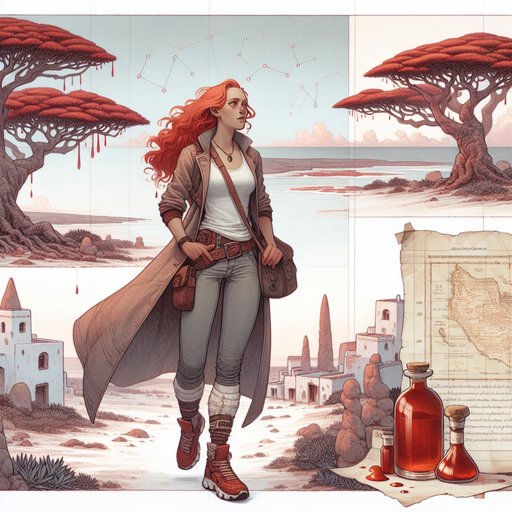

Barbra Dender, a 31-year-old red-haired traveler with a quiet resilience born from being raised by her grandparents, sets out to a place she has never been: Socotra, the island of dragon’s blood trees and salt-scented wind. She rents a simple room above a perfumer’s shop in Hadibo, where the air hangs heavy with resin and citrus. Dressed in her usual tight jeans, blue and white Asics, and a tank top, with one of her favorite jackets for the ocean chill, she spends her days walking long distances across wind-scoured plateaus and empty beaches, drawn to phenomena she does not understand. Stone cairns match constellations; resin beads on a tree seem to gather into script; salt pans echo the arabesques of maps. The perfumer’s family is kind yet guarded, their silences hinting at a centuries-old secret tied to the island’s incense trade. By showing integrity and patience, Barbra slowly earns their trust. Her first real clue arrives when a purchase is wrapped in a scrap of old ledger paper stained in red resin, revealing a fragmentary map and a cryptic note about a ‘salt road’ and a ‘singing cave.’ As dusk gathers, she aligns the scrap with the horizon and senses the path pointing toward Hoq Cave. The chapter ends on a cliffhanger as she wonders who has been guarding the secret and whether the cave will open its story to her.

The plane banked low over a ribbon of turquoise, and Barbra Dender leaned toward the oval window, her red hair catching the sun like a small, stubborn fire. Heat-warped islands unspooled beneath her, dun and green, pricked with trees that looked like umbrellas turned inside out. She touched the bridge of her nose where freckles clustered, those constellations she never learned to love, and smiled despite herself at the thought of a new place. At thirty-one, with a lifetime of long walks behind her and a glass cabinet of artifacts awaiting her return at home, she felt that particular flutter that meant a mystery was near.

She had never been to Socotra, and something about the name itself sounded like a promise kept in a hollow of stone. She stepped onto the tarmac in tight jeans and her blue and white Asics sneakers, a white tank top under a faded floral denim jacket that handled spray and breeze better than leather. The air smelled of salt and resin and faint citrus, a scent that felt both ancient and clean. Taxis nudged forward like patient goats, and the road to Hadibo curled along an edge of sea that unrolled in dazzling sheets.

Barbra barely wore makeup; she did not need it, though she never believed people who told her so, and she pushed a stray red strand behind one ear as if that gesture alone might quiet her doubts. When she passed a storefront window and caught sight of her freckles, she frowned at them as at an old joke she refused to laugh at. Her temporary home was a small room above a perfumer’s shop near the market, two streets back from the port where wooden boats tapped the quay. The shop was a cave of glass and shadow, lined with bottles like trapped sunsets and jars of resin the color of dried blood.

A ceiling fan moved the heat in soft circles; the scent of frankincense, myrrh, and dragon’s blood hung in every slat and thread. From her balcony she could see goats skirting sacks of salt and fishermen lifting their nets as if the sea was a heavy curtain. She set her backpack on the bed, looked out across the roofs, and felt the same restless contentment that had settled over her since childhood, when solitude had ceased to be absence and became a companion. She had been four when her parents died, and her grandparents—stern hands, warm soup, quiet gardens—taught her the art of doing without complaint.

She learned to tie her own laces and read the weather on a walk, to keep questions in her pocket until the right person or the right silence arrived to answer them. Now, whenever she traveled, those lessons rose like a calm tide behind her steps. The glass wall cabinet at home bristled in her mind with brass tokens, chalky shards, a coil of wire pulled from a buried fence, each a chapter anchor. She intended to come back with only one thing, if anything, and only with permission, but already her fingers itched for the shape of whatever Socotra would offer.

On her first morning she walked before the sun got loud, leaving the market’s bustle for a track that lifted into limestone hills. The path was crusted with salt like sugar on a pastry, and in flats between rocks little bottle-shaped trees bloomed with impossible pink. Farther on, high as a held breath, the dragon’s blood trees waited, their canopies plates upon plates like stacked thoughts. As she climbed, the sea became a strip of metal light, and the wind began to speak in a low stitching sound that made her feel as if someone were mending the day around her.

Barbra’s legs were strong from years of long walks, and the rhythmic work of it eased her into attention. She reached the plateau and went still. The dragon’s blood trees bled resin in beadlike tears that crusted into rubescent bulbs, and in certain drips, where sun and wind had cured them unevenly, the surface pitted into neat ovals, as if punched by a tiny, relentless hand. Nearby, someone had arranged small stones into lines and arcs that echoed again and again, as if reproducing a pattern from memory.

It did not look like a tourist’s whim; it was too consistent, too sure. She crouched to trace an arc with her thumb and felt grit and warmth and the faint tack of resin, like a fingertip pressed to sealing wax. When she descended in late afternoon, dust-laced and salt-tongued, the perfumer raised his eyes and nodded in greeting. He was maybe her age, with a mapmaker’s patience in his movements, and he introduced himself as Salem, gesturing toward an elderly woman in the back room who stitched cloth sachets for resin.

Things here were offered with straightforward grace: tea in a high glass, a chair in the shady doorway, no questions she did not want to answer. But when she mentioned the stone arcs, a silence dipped between them, not hostile, just careful. Salem smiled, gentle as a lock turned under a cloth, and asked instead whether the climb had been hot. That night, the shop’s scents climbed the stairs and gathered in her room, and sleep came like a boat tied to a quivering dock.

Barbra lay awake for a while, toying with a loose thread on her jacket cuff, thinking of her grandparents and how her grandmother had lined the pantry shelves with brown paper and labels in looping, stubborn script. She thought of the men at the port, the goats dodging the slick scales thrown out by laughing boys, the weight of her freckles visible even in the dark. Love sat in her memory like a sparkler burnt down to a wire, bright, quick, gone; she had long accepted that travel and a slower burn were her better pair. She rose before dawn, restless to walk the pattern until it gave something up.

Over the next days she did not press Salem or the grandmother, whom he called Amina. She bought little things that would not fill her pack: a small vial of citrus essence, a square of dyed cloth, a handful of almond sweets wrapped in shining foil. She offered to help arrange the shelves, and Amina watched her handle the jars with care, once touching Barbra’s forearm with the wise, brief gesture of someone who understood steadiness when she saw it. In that exchange, trust loosened the room a fraction, enough that threads of story began to show.

People had always told Barbra things they did not plan to; it was her quiet, her willingness to be the person who could carry a secret without breaking it. A fisherman told her about a cave in the north, its walls covered in names left by sailors long dead, inscriptions like a long, multiplex choir. Another woman in the market muttered about a road made of nothing you could see, followed by those who knew how to read salt the way birds read wind. She heard the words singing cave more than once and did not pretend to misunderstand; instead she stored the phrase in her mental cabinet, beside the arc of stones and the resin’s dotted ovals.

On one afternoon walk she encountered more stone patterns, aligned to a cleft between two crags, a sightline as deliberate as a ship’s prow. The wind coming through the bottle trees keened a tone like a tuning fork, and she felt it along her teeth. At low tide she went east toward flats that flashed white under the sun, the salt pans crusted and crazed like old porcelain. Workers carved the crust into squares, and in runoff channels the crystals gathered in threads and loops, repeating curls that looked like calligraphy.

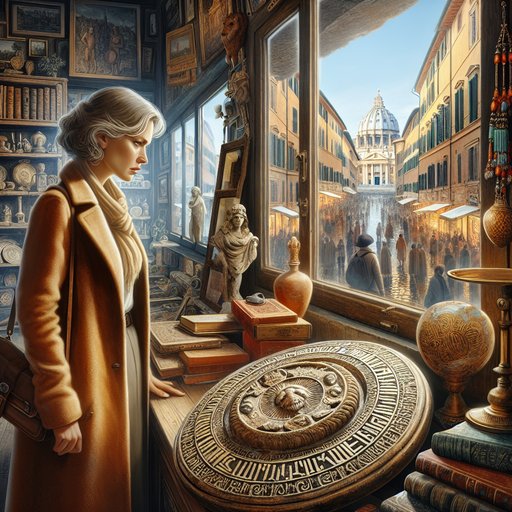

Kneeling, Barbra sketched the curves into her notebook, comparing them against the stone arcs in her mind’s eye. A boy with hair bleached ragged by sun paused near her and looked at her drawing with a solemnity that made him appear briefly older than his small bones. He traced with his finger a spiral on his own palm and then ran off, dropping a shell carved with a similar curve that caught the light like a wink. Back at the perfumer’s, the day’s heat balled into corners while Amina measured resin into brown paper cones.

The paper came from an old ledger, edges furred, ink faded to a thirsty sepia. When Barbra bought a sachet, Amina reached for another scrap, and the piece she used had lines drawn on it, thin and cunning as hair. Barbra saw at once that it was a map fragment—coastline wreathed in hatch marks, a diagonal line pointing inland toward a notch like a bitten cookie—and a smear of red made dots along the line at intervals. Between the dots there were three words in a small, stubborn hand: Follow the salt road.

Amina froze, and her fingers tightened around the paper, then loosened. Something passed over her face that was not fear so much as the sternness of someone guarding a door she had stood before for decades. She folded the paper around the resin as if it were a packet of tea, placed it in Barbra’s palm with a weight beyond its measure, and inclined her head. Salem’s eyes moved from the packet to Barbra and back again, and after a long breath he said, not to her but to the room, that the cave had many names and not all of them sang.

The fan clicked once, twice, a tired metronome above them, marking the switch of a tide no one acknowledged. At dusk Barbra climbed the short path to an old Portuguese watchtower on a hill that gave her a view of the northern ridge. The stones still remembered hands, and the tower’s slit windows framed the mountains like records in a shelf. She opened the packet and smoothed the ledger scrap against her knee, aligning the hand-drawn coastline with the real metal line of sea below.

The red dots ran straight to a cleft that corresponded with the route toward Hoq Cave, which she had traced on another map she kept folded in her pack since landing. The wind rose, and from the direction of the ridge came a low humming, not music and not quite wind, a sound like a vessel set ringing by a finger. Barbra stood with the paper in hand, her freckles catching the last light like the stars in a chart someone had once taught her to read without words. The salt road, the stone arcs, the resin’s dotted script, the carved shell, and the phrase singing cave all slotted together with a snugness that left no room for accident.

She felt the old excitement, the respectful hush that came when a secret stretched awake and peered at her through slitted rock. Her long legs thrummed with the desire to begin the climb before dawn, to test the humming, to see if names barely remembered might speak to her in chalk and damp air. But who would be waiting in that cleft, who had been keeping this path, and would the cave open its story to her or seal it shut the moment she approached?