- Details

- Written by: Valenenzia Gruelle

The week began with a simple, unassailable truth returning to headlines: teachers are the key to students’ AI literacy—and they need support to do the job well [1]. In a season of breathless product launches and policy whiplash, that reminder is less a slogan than a societal checkpoint. If we want classrooms to be where democratic competence with intelligent tools is cultivated rather than corroded, we must equip the educators who steward them. Everything else is vapor.

- Details

- Written by: Anne Wienbloch

New trailers for The Ugly — a Korean thriller from the director of Train to Busan — have arrived, and they lean hard into the film’s preoccupation with memory [3][2]. Trailers are never neutral; they are cultural instruments that prime expectations, anxieties, and, crucially, policy instincts. In a season when institutions are quick to add warnings or gates, the arrival of a memory-obsessed thriller invites a familiar question with fresh stakes: when do we protect audiences, and when do we slip into policing their imaginations? The conversation is bigger than one film, but The Ugly gives us a sharp lens: if memory is fragile and constructed, then attempts to shield us can accidentally sand it down — and that, too, is a form of forgetting [2].

- Details

- Written by: Bob Fratenni

American Samoa has said no to deep-sea mining, but the Trump administration might do it anyway—a collision of local consent and imperial habit that lays bare how modern extractive appetites treat oceans as sacrifice zones [2]. The Pacific’s once-united front on climate action is itself splintering over deep-sea mining, signaling a political riptide that powerful actors are eager to ride [1][5]. Meanwhile, new deep-ocean facilities and feasibility studies elsewhere feed a narrative of inevitability: dig because we can, and because someone else will if we don’t [3][6]. When a river turns toxic, it is a mirror held up to our consumption habits; the seabed is simply the next mirror, darker and deeper. The question now is whether outrage can harden into regulation and restorative justice before silence descends on ecosystems we barely understand.

- Details

- Written by: Valenenzia Gruelle

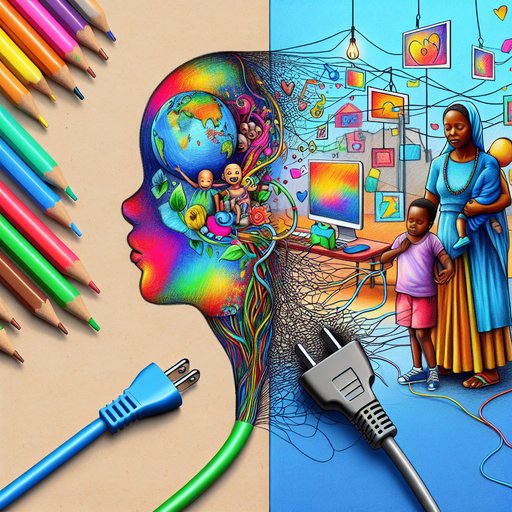

Melaka’s Graphytoon promises a small miracle: take a child’s crayon sketch and let artificial intelligence set it in motion, turning young art into animated stories [5]. The spectacle is delightful—and disarming. When software starts co‑authoring childhood, the core question isn’t merely what the algorithm can do, but who it serves, who it listens to, and who is left voiceless as daily life becomes a negotiation with code. In a world where whole populations still struggle for basic connectivity, the risks of exclusion are not abstract; African women, for example, have less access to the internet than men [1]. Graphytoon is a charming case with serious stakes: it asks whether we will design the next generation of creative tools as engines of inclusion or as silent editors of children’s imaginations.