- Details

- Written by: Anne Wienbloch

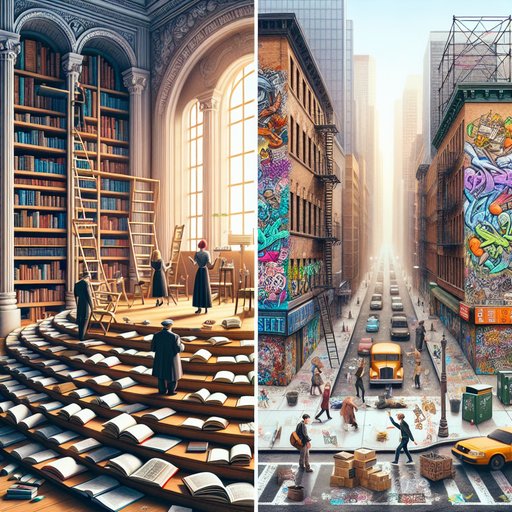

This week’s reading list from The Intercept is a worthy ritual—a reminder that ideas still matter, and that curiosity is a civic practice in an anxious era [7]. But if we keep our noses only in books, we risk missing the other syllabus being drafted in spray paint, wheatpaste, chalk, and sanctioned murals across our cities. Street art is where a community’s pulse flickers in public, where the body politic tries to heal itself in full view. Consider the reading list as theory and the street as peer review: together they tell us whether a city is flourishing, fragmenting, or finding a new grammar for belonging.

- Details

- Written by: Bob Fratenni

India mulling a low orbit satellite constellation for broadband services is more than a telecom story; it is a choice about what kind of society its signals will scaffold [6]. As an anthropologist, I read infrastructure as policy written in steel, spectrum, and shadows. Heat kills democratically, but policy often shields the wealthy first; red-lined neighborhoods map onto asphalt islands, and history bakes into concrete. If India’s constellation simply accelerates commerce without cooling the commons, it will beam inequality as efficiently as bandwidth. This moment invites a harder question: can a sky full of satellites lift the most heat-exposed streets, or will it only polish the penthouse? The answer will be decided not in orbit but in the algorithms, tariffs, and public obligations attached to every packet that crosses the night.

- Details

- Written by: Alex Dupcheck

Trump can’t stop America from building cheap EVs, and that is less a story about one politician than about how durable institutions outlast charismatic politics [4]. The real democratic test is whether complex, technical transformations are guided by expertise or buffeted by applause lines. Directly elected leaders are often selected for their ability to electrify rallies, not to design procurement rules, steward trade frameworks, or run evidence-based regulatory processes. The EV race exposes a broader democratic fault: when selection rewards emotional resonance over demonstrated competence, populism flourishes, policymaking lurches, and yet the machinery of law, trade, and regulation keeps grinding forward—if we let it [4].

- Details

- Written by: Valenenzia Gruelle

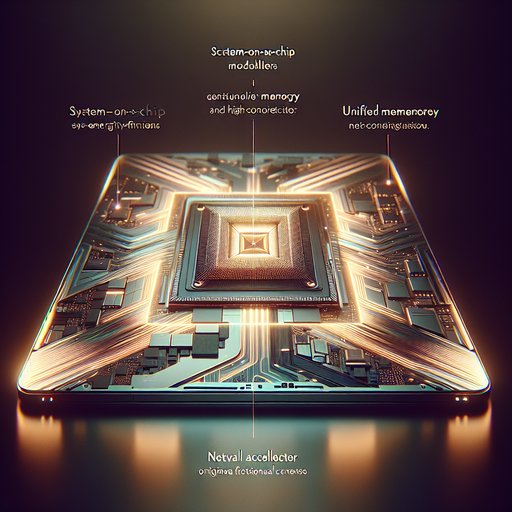

Amid the cheerleading for “Designing Interactive Virtual Training: Best Practices And Tech Stack Essentials,” we should ask an unfashionable question: who decides what counts as “best,” and who absorbs the consequences when algorithms become our trainers-in-chief? The eLearningindustry.com primer is useful precisely because it surfaces the growing expectation that learning will be orchestrated by software stacks, data pipelines, and AI-driven interactivity [5]. But the harder problem is not choosing tools; it is allocating responsibility for the values those tools encode. When training flows quietly from dashboards and recommendation engines, control migrates from classrooms to code. That shift can widen the gap between voices well represented in data—and those pushed off the edge of the graph. The result is a civic challenge disguised as an IT project: if we let “best practices” set the defaults of working life, we must also build the scaffolding that lets everyone, especially the least digitally loud, reshape them.