I have lived long enough under lifts to hear the language of cars change. The clatter of tappets gave way to the hiss of injectors, then the murmur of inverters. It wasn’t sudden. It arrived like a new tool in the bottom drawer — a thing you don’t trust until it saves your knuckles. From leaded days and carb jets to software updates and high-voltage isolation checks, I’ve watched the shift from combustion to electric in the most practical place possible: a shop bay that smells like hot rubber and coffee that’s gone cold.

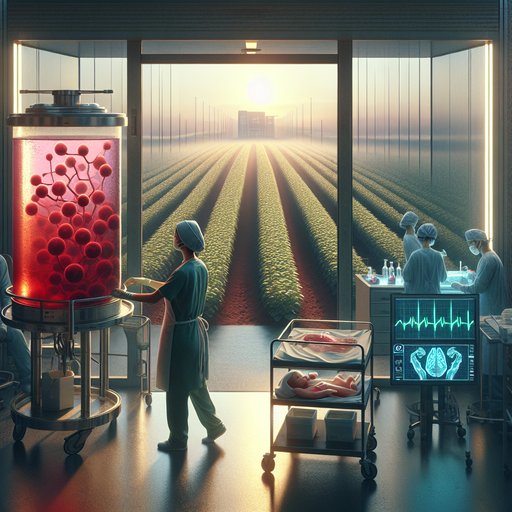

In a hospital room that smells faintly of antiseptic and citrus cleaner, a nurse wheels in a bag of a patient’s own blood stem cells—now edited with a molecular scalpel that was a lab curiosity just a decade ago. At another hospital, surgeons watch a gene-edited pig kidney pink up inside a human body, while cameras catch the moment a machine learning model proposes a safer way to make a change in DNA without breaking the strand clean through. In farm plots marked by colored flags, seedlings bred by precision rather than cross-pollination rise into heat that does not let up. The breakthroughs of the past year do not announce themselves with triumphal fanfare so much as the hum of pumps, the glow of monitors, and the quiet recalibration of what medicine, agriculture, and biology expect from the alphabet of life.

The new creative handshake happens in the half‑light of screens: a human sketches intent in a sentence, and a model replies with images, copy, code, or melody. What began as a research curiosity has slipped into daily workflows, remapping how ideas move from brief to product and how businesses price speed itself. Generative AI is not just a tool; it behaves like a studio assistant with infinite stamina, an analyst who reads everything, a sales rep who never sleeps. Its rise is neither sudden nor simple. It echoes decades of experiments in machine creativity, now amplified by transformers and cheap cloud muscle, and it forces a negotiation—between imagination and automation, originality and scale, authorship and efficiency—that will define the next economy.

When Buddy Holly stepped under The Ed Sullivan Show’s lights in December 1957, cradling a sunburst Fender Stratocaster, a new American sound gained a national stage. His chiming, assertive tone, the crystalline snap of a three-pickup guitar, and an unpretentious presence combined to make rock ’n’ roll feel both accessible and unstoppable. The Stratocaster’s modern silhouette reflected postwar optimism, and Holly’s easy confidence suggested that a teenager with the right chords could speak to the whole country. What happened that night didn’t invent rock ’n’ roll, but it demonstrated how a mass democracy could carry a regional spark into millions of living rooms—and how institutions, audiences, and artists would immediately begin negotiating the boundaries of this noisy, democratic art.